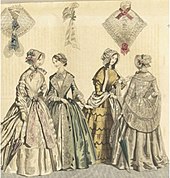

Pictures of Late 1800s Girls Fashion

Illustration depicting fashions throughout the 19th century

Victorian fashion consists of the diverse fashions and trends in British culture that emerged and developed in the United Kingdom and the British Empire throughout the Victorian era, roughly from the 1830s through the 1890s. The catamenia saw many changes in fashion, including changes in styles, fashion technology and the methods of distribution. Various movement in compages, literature, and the decorative and visual arts as well as a changing perception of gender roles also influenced fashion.

Nether Queen Victoria's reign, England enjoyed a period of growth forth with technological advancement. Mass production of sewing machines in the 1850s equally well as the advent of synthetic dyes introduced major changes in style.[1] Vesture could be made more quickly and cheaply. Advancement in printing and proliferation of fashion magazines allowed the masses to participate in the evolving trends of high style, opening the market of mass consumption and advertising. Past 1905, article of clothing was increasingly mill made and oft sold in large, stock-still-price section stores, spurring a new age of consumerism with the rising middle class who benefited from the industrial revolution.[i]

Women's fashions

During the Victorian Era, women generally worked in the private, domestic sphere.[2] Unlike in before centuries when women would oftentimes aid their husbands and brothers in family businesses and in labour, during the nineteenth century, gender roles became more defined. The requirement for farm labourers was no longer in such a high demand after the Industrial Revolution, and women were more likely to perform domestic work or, if married, give up piece of work entirely. Dress reflected this new, increasingly sedentary lifestyle, and was non intended to be commonsensical.

Apparel were seen as an expression of women's place in gild,[3] hence were differentiated in terms of social class. Upper-class women, who did not need to work, often wore a tightly laced corset over a bodice or chemisette, and paired them with a skirt adorned with numerous embroideries and trims; over layers of petticoats. Middle-grade women exhibited like apparel styles; all the same, the decorations were non as extravagant. The layering of these garments make them very heavy. Corsets were likewise stiff and restricted movement. Although the clothes were not comfortable, the type of fabrics and the numerous layers were worn as a symbol of wealth.

Picture of 1850s evening apparel with a bertha neckline

- Neck-line: Bertha is the low shoulder neck-line worn past women during the Victorian Era. The cut exposed a adult female'due south shoulders and information technology sometimes was trimmed over with a three to half-dozen-inch deep lace flounce, or the bodice has neckline draped with several horizontal bands of material pleats. However, the exposure of neck-line was only restricted to the upper and middle class, working-class women during the fourth dimension period were not allowed to reveal and so much flesh.

The décolleté style made shawls to become an essential characteristic of dresses. Corsets lost their shoulder straps, and mode was to produce two bodices, one closed décolletage for day and 1 décolleté for evening.

- Boning: Corsets were used in women's gowns for emphasizing the minor waist of the female person trunk. They role every bit an undergarment which can be adjusted to bind tightly around the waist, hold and train a person'due south waistline, so to slim and conform it to a fashionable silhouette. It also helped stop the bodice from horizontal creasing. With the corset, a very small tight fitting waist would exist shown.

Corsets have been blamed for causing many diseases because of tight lacing, just the practice was less commonplace than generally thought today (Furnishings of tightlacing on the torso).

- Sleeves: Sleeves were tightly fit during the early Victorian era. It matched with the tight fit women's small waist in the blueprint, and the shoulder sleeve seamline was drooped more to show a tighter fit on the arm. This eventually limited women's movements with the sleeves.

However, as crinolines started to develop in fashion, sleeves turned to be similar big bells which gave the dress a heavier volume. Engageantes, which were usually fabricated of lace, linen, or backyard, with cambric and broderie anglaise, were worn under the sleeves. They were easy to remove, launder and restitch into position, so to act as fake sleeves, which was tacked to the elbow-length sleeves during the time. They commonly announced under the bell-shaped sleeves of 24-hour interval dresses.

- Gloves: Considering tanned, blackness easily were considered the color of the working class and not beautiful, upper class women often wore gloves. Long opera gloves were worn with short-sleeved or sleeveless dresses. Long gloves concealed the skin on the arms and helped women maintain their modesty.[4]

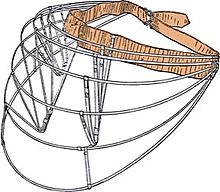

- Silhouette: Silhouette changed over time supported by the development of the undergarment. In earlier days, wide skirts were supported by fabrics like linen which used horsehair in the weave. Crinolines were used to give skirts a beehive shape, with at least half dozen layers petticoats worn under the skirt, which could weigh as much as fourteen pounds. Afterward, the cage crinoline was developed. Women were freed from the heavy petticoats, and were able to motility their legs freely beneath the muzzle. Silhouette afterward began to emphasise a slope toward the back of the brim. Polonaise style was introduced where fullness bunched up at the dorsum of the brim. Crinolines and cages also started to disappear with it being more dangerous to working-class women. Tournures or bustles were developed.

Victorian-era cosmetics were typically minimal, equally makeup was associated with promiscuity. Many cosmetics independent toxic or caustic ingredients like lead, mercury, ammonia, and arsenic.

1830s clothes style

During the get-go of Queen Victoria'due south reign in 1837, the platonic shape of the Victorian woman was a long slim torso emphasised by wide hips. To achieve a low and slim waist, corsets were tightly laced and extended over the abdomen and downwardly towards the hips.[5] A chemise was ordinarily worn under the corset, and cut relatively low in lodge to foreclose exposure. Over the corset, was the tight-plumbing fixtures bodice featuring a low waistline. Forth with the bodice was a long skirt, featuring layers of horsehair petticoats[5] worn underneath to create fullness; while placing emphasis on the small waist. To contrast the narrow waist, depression and straight necklines were thus used.

1840s clothes way

In the 1840s, collapsed sleeves, depression necklines, elongated V-shaped bodices, and fuller skirts characterised the dress styles of women.

At the showtime of the decade, the sides of bodices stopped at the natural waistline, and met at a point in the front. In accordance with the heavily boned corset and seam lines on the bodice as well, the popular low and narrow waist was thus accentuated.

Sleeves of bodices were tight at the top, considering of the Mancheron,[6] merely expanded around the surface area between the elbow and before the wrist. It was also initially placed below the shoulder, however; this restricted the movements of the arm.[6]

As a event, the centre of the decade saw sleeves flaring out from the elbow into a funnel shape; requiring undersleeves to exist worn in club to cover the lower arms.[7]

Skirts lengthened, while widths increased due to the introduction of the horsehair crinoline in 1847; becoming a condition symbol of wealth.

Extra layers of flounces and petticoats, also farther emphasised the fullness of these wide skirts. In compliance with the narrow waist though, skirts were therefore attached to bodices using very tight organ pleats secured at each fold.[6] This served as a decorative element for a relatively evidently skirt. The 1840s style was perceived equally conservative and "Gothic" compared to the flamboyance of the 1830s.[8]

1850s dress way

A like silhouette remained in the 1850s, while certain elements of garments changed.

Necklines of day dresses dropped even lower into a V-shape, causing a demand to cover the bust area with a chemisette. In contrast, evening dresses featured a Bertha, which completely exposed the shoulder area instead. Bodices began to extend over the hips, while the sleeves opened further and increased in fullness. The book and width of the brim continued to increment, especially during 1853, when rows of flounces were added.

All the same, in 1856, skirts expanded even further; creating a dome shape, due to the invention of the start artificial cage crinoline. The purpose of the crinoline was to create an artificial hourglass silhouette by accentuating the hips, and fashioning an illusion of a pocket-size waist; along with the corset. The muzzle crinoline was constructed by joining thin metal strips together to course a circular structure that could solely back up the large width of the brim. This was made possible past technology which allowed iron to be turned into steel, which could so exist drawn into fine wires.[1] Although oft ridiculed by journalists and cartoonists of the fourth dimension as the crinoline swelled in size, this innovation freed women from the heavy weight of petticoats and was a much more aseptic option.[8]

Meanwhile, the invention of constructed dyes added new colours to garments and women experimented with gaudy and bright colours. Technological innovation of 1860s provided women with freedom and choices.[one]

1860s wearing apparel style

1860s clothes featuring a train

During the early and centre 1860s, crinolines began decreasing in size at the pinnacle, while retaining their amplitude at the bottom.[9] In contrast, the shape of the crinoline became flatter in the front end and more voluminous behind, as information technology moved towards the dorsum since skirts consisted of trains at present. Bodices on the other mitt, concluded at the natural waistline, had broad pagoda sleeves, and included high necklines and collars for 24-hour interval dresses; depression necklines for evening dresses. However, in 1868, the female person silhouette had slimmed downwards as the crinoline was replaced past the bustle, and the supporting flounce overtook the part of determining the silhouette.[10] Skirt widths macerated fifty-fifty further, while fullness and length remained at the back. In order to emphasise the back, the train was gathered together to form soft folds and draperies[xi]

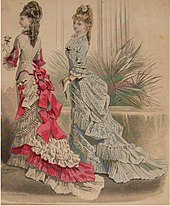

1870s wearing apparel style

The trend for wide skirts slowly disappeared during the 1870s, as women started to prefer an even slimmer silhouette. Bodices remained at the natural waistline, necklines varied, while sleeves began nether the shoulder line. An overskirt was commonly worn over the bodice, and secured into a large bow behind. Over time though, the overskirt shortened into a detached basque, resulting in an elongation of the bodice over the hips. As the bodices grew longer in 1873, the polonaise was thus introduced into the Victorian dress styles. A polonaise is a garment featuring both an overskirt and bodice together. The tournure was too introduced, and along with the polonaise, it created an illusion of an exaggerated rear end.

By 1874, skirts began to taper in the front and were adorned with trimmings, while sleeves tightened around the wrist area. Towards 1875 to 1876, bodices featured long but fifty-fifty tighter laced waists, and converged at a precipitous indicate in front. Bustles lengthened and slipped even lower, causing the fullness of the skirt to further diminish. Actress textile was gathered together backside in pleats, thus creating a narrower but longer tiered, draped train too. Due to the longer trains, petticoats had to exist worn underneath in club to go on the clothes clean.

However, when 1877 approached, dresses moulded to fit the effigy,[9] every bit increasing slimmer silhouettes were favoured. This was allowed by the invention of the cuirass bodice which functions like a corset, but extends downwards to the hips and upper thighs. Although dress styles took on a more than natural class, the narrowness of the brim limited the wearer in regards to walking.

1880s wearing apparel style

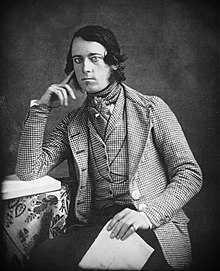

A Victorian dandy pictured in the 1840s

The early on 1880s was a period of stylistic confusion.[1] On i paw, in that location is the over-ornamented silhouette with contrasting texture and frivolous accessories. On the other hand, the growing popularity of tailoring gave ascent to an alternative, astringent manner.[viii] Some credited the change in silhouette to the Victorian dress reform, which consisted of a few movements including the Aesthetic Costume Move and the Rational Wearing apparel Move in the mid-to-late Victorian Era advocating natural silhouette, lightweight underwear, and rejecting tightlacing. Nonetheless, these movements did not gain widespread back up. Others noted the growth in cycling and tennis every bit acceptable feminine pursuits that demanded a greater ease of movement in women's clothing.[1] Even so others argued that the growing popularity of tailored semi-masculine suits was simply a fashionable style, and indicated neither advanced views nor the demand for practical clothes.[8] However, the diversification in options and adoption of what was considered menswear at that time coincided with growing ability and social status of women towards the belatedly-Victorian period.

The bustle made a re-appearance in 1883, and it featured a farther exaggerated horizontal protrusion at the back. Due to the additional fullness, mantle moved towards the sides or front panel of the skirt instead. Any drape at the dorsum was lifted upwardly into poufs. Bodices on the other manus, shortened and ended higher up the hips. Yet the mode remained tailored, but was more than structured.

However, by 1886, the silhouette transformed back to a slimmer figure again. Sleeves of bodices were thinner and tighter, while necklines became higher over again. Furthermore, an even further tailored-look began to develop until it improved in the 1890s.

1890s dress mode

Past 1890, the crinoline and bustle was fully abandoned, and skirts flared away naturally from the wearer's tiny waist. It evolved into a bell shape, and were made to fit tighter around the hip area. Necklines were high, while sleeves of bodices initially peaked at the shoulders, just increased in size during 1894. Although the large sleeves required cushions to secure them in place, information technology narrowed down towards the end of the decade. Women thus adopted the style of the tailored jacket, which improved their posture and confidence, while reflecting the standards of early female person liberation.

Hats

Hats were crucial to a respectable appearance for both men and women. To go bareheaded was but not proper. The top hat, for example, was standard formal article of clothing for upper- and middle-class men.[8] For women, the styles of hats changed over time and were designed to lucifer their outfits.

During the early Victorian decades, voluminous skirts held up with crinolines, and so hoop skirts, were the focal point of the silhouette. To enhance the style without distracting from it, hats were modest in size and design, straw and fabric bonnets being the popular choice. Poke bonnets, which had been worn during the late Regency period, had high, small crowns and brims that grew larger until the 1830s, when the face up of a adult female wearing a poke bonnet could but be seen directly from the front end. They had rounded brims, echoing the rounded form of the bell-shaped hoop skirts.

The silhouette inverse one time once more as the Victorian era drew to a close. The shape was substantially an inverted triangle, with a broad-brimmed hat on top, a total upper body with puffed sleeves, no bustle, and a skirt that narrowed at the ankles[12] (the hobble skirt was a fad soon after the cease of the Victorian era). The enormous broad-brimmed hats were covered with elaborate creations of silk flowers, ribbons, and above all, exotic plumes; hats sometimes included entire exotic birds that had been stuffed. Many of these plumes came from birds in the Florida everglades, which were nearly made entirely extinct past overhunting. By 1899, early on environmentalists like Adeline Knapp were engaged in efforts to curtail the hunting for plumes. Past 1900, more than than five 1000000 birds a yr were beingness slaughtered, and nigh 95 percent of Florida's shore birds had been killed by plume hunters.[13]

Shoes

The women'south shoes of the early Victorian period were narrow and heelless, in black or white satin. By 1850s and 1860s, they were slightly broader with a low heel and fabricated of leather or cloth. Ankle-length laced or buttoned boots were also pop. From the 1870s to the twentieth century, heels grew higher and toes more pointed. Depression-cutting pumps were worn for the evening.[eight]

Men's fashion

Drawing of Victorian men 1870s

During the 1840s, men wore tight-fitting, calf length frock coats and a waistcoat or belong. The vests were unmarried- or double-breasted, with shawl or notched collars, and might be finished in double points at the lowered waist. For more than formal occasions, a cutaway morning coat was worn with lite trousers during the daytime, and a dark tail coat and trousers was worn in the evening. Shirts were made of linen or cotton with low collars, occasionally turned down, and were worn with broad cravats or neck ties. Trousers had fly fronts, and breeches were used for formal functions and when horseback riding. Men wore top hats, with broad brims in sunny weather.

During the 1850s, men started wearing shirts with high upstanding or turnover collars and four-in-hand neckties tied in a bow, or tied in a knot with the pointed ends sticking out like "wings". The upper-class continued to habiliment tiptop hats, and bowler hats were worn by the working class.

In the 1860s, men started wearing wider neckties that were tied in a bow or looped into a loose knot and fastened with a stickpin. Frock coats were shortened to genu-length and were worn for business, while the mid-thigh length sack coat slowly displaced the apron coat for less-formal occasions. Top hats briefly became the very tall "stovepipe" shape, but a variety of other chapeau shapes were popular.

During the 1870s, three-piece suits grew in popularity forth with patterned fabrics for shirts. Neckties were the four-in-hand and, later on, the Ascot ties. A narrow ribbon necktie was an culling for tropical climates, particularly in the Americas. Both frock coats and sack coats became shorter. Flat straw boaters were worn when boating.

During the 1880s, formal evening dress remained a dark tail coat and trousers with a dark waistcoat, a white bow tie, and a shirt with a winged collar. In mid-decade, the dinner jacket or tuxedo, was used in more than relaxed formal occasions. The Norfolk jacket and tweed or woolen breeches were used for rugged outdoor pursuits such as shooting. Articulatio genus-length topcoats, often with contrasting velvet or fur collars, and calf-length overcoats were worn in winter. Men's shoes had higher heels and a narrow toe.

Starting from the 1890s, the blazer was introduced, and was worn for sports, sailing, and other casual activities.[fourteen]

Throughout much of the Victorian era most men wore fairly short pilus. This was ofttimes accompanied by diverse forms of facial hair including moustaches, side-burns, and full beards. A clean-shaven face did not come back into fashion until the terminate of the 1880s and early 1890s.[15]

Distinguishing what men really wore from what was marketed to them in periodicals and advertisements is problematic, every bit reliable records practise non exist.[16]

Mourning black

Victoria's five daughters (Alice, Helena, Beatrice, Victoria and Louise), photographed wearing mourning black beneath a bust of their late father, Prince Albert (1862)

In Britain, blackness is the colour traditionally associated with mourning for the dead. The community and etiquette expected of men, and especially women, were rigid during much of the Victorian era. The expectations depended on a complex bureaucracy of shut or distant relationship with the deceased. The closer the human relationship, the longer the mourning menstruum and the wearing of black. The wearing of full black was known as First Mourning, which had its own expected attire, including fabrics, and an expected duration of 4 to 18 months. Following the initial period of Outset Mourning, the mourner would progress to 2d Mourning, a transition period of wearing less black, which was followed by Ordinary Mourning, and so Half-mourning. Some of these stages of mourning were shortened or skipped completely if the mourner's relationship to the deceased was more than distant. One-half-mourning was a transition period when black was replaced past acceptable colours such as lavender and mauve, maybe considered acceptable transition colours considering of the tradition of Church of England (and Cosmic) clergy wearing lavender or mauve stoles for funeral services, to correspond the Passion of Christ.[17]

The mourning dress on the correct was worn past Queen Victoria, "it shows the traditional touches of mourning attire, which she wore from the death of her husband, Prince Albert (1819–1861), until her own death."[18]

Norms for mourning

Manners and Rules of Good Society, or, Solecisms to be Avoided (London, Frederick Warne & Co., 1887) gives clear instructions, such as the following:[nineteen]

| Human relationship to deceased | Beginning mourning | 2nd mourning | Ordinary mourning | Half-mourning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wife for husband | i-year, 1-month; bombazine fabric covered with crepe; widow's cap, lawn cuffs, collars | 6 months: less crepe | 6 months: no crepe, silk or wool replaces bombazine; in final 3 months jet jewellery and ribbons tin can be added | half dozen months: colours permitted are grey, lavender, mauve, and black-and-grey |

| Girl for parent | vi months: black with black or white crepe (for immature girls); no linen cuffs and collars; no jewellery for offset two months | four months: less crepe | – | ii months equally above |

| Wife for husband's parents | 18 months in blackness bombazine with crepe | – | 3 months in black | 3 months as higher up |

| Parent for son- or daughter-in-law's parent | – Black armband in representation of someone lost | – | 1-calendar month black | – |

| 2d wife for parent of a commencement wife | – | – | 3 months blackness | – |

The complexity of these etiquette rules extends to specific mourning periods and attire for siblings, step-parents, aunts and uncles distinguished by claret and by marriage, nieces, nephews, starting time and second cousins, children, infants, and "connections" (who were entitled to ordinary mourning for a period of "1–iii weeks, depending on level of intimacy"). Men were expected to wear mourning black to a lesser extent than women, and for a shorter mourning period. Later on the mid-19th century, men would wearable a black hatband and blackness suit, only for merely one-half the prescribed period of mourning expected of women. Widowers were expected to mourn for a mere three months, whereas the proper mourning flow expected for widows was up to four years.[20] Women who mourned in black for longer periods were accorded neat respect in public for their devotion to the departed, the most prominent instance being Queen Victoria herself.

Women with lesser financial means tried to go along upward with the example beingness set by the centre and upper classes by dyeing their daily wearing apparel. Dyers made most of their income during the Victorian period by dyeing wearing apparel black for mourning.[21]

Technological advocacy

Technological advancements not but influenced the economy merely brought a major change in the fashion styles worn by men and women. Equally the Victorian era was based on the principles of gender, race and class.[22] Much advancement was in favor of the upper class as they were the ones who could afford the latest technology and change their fashion styles accordingly. In 1830s there was introduction of horse hair crinoline that became a symbol of condition and wealth every bit only the upper-class women could wear it. In 1850s there were more than fashion technological advancements hence 1850s could rightly be chosen a revolution in the Victorian style industry such as the innovation of artificial cage crinoline that gave women an artificial hourglass silhouette this meant that women did not have to wear layers of petticoats anymore to achieve illusion of wide hips and it was also hygienic.[23] Synthetic dyes were also introduced that added new bright colours to garments. These technological advocacy gave women liberty and choices. In 1855's Haute couture was introduced as tailoring became more mainstream in years to follow.[24]

Charles Frederick Worth, a prominent English language designer, became popular among the upper class though its city of destiny ever is Paris. Haute couture became pop at the aforementioned time when sewing machines were invented.[25] Hand sewn techniques arose and were a stardom in compared to the old ways of tailoring. Princess Eugenie of France wore the Englishman dressmaker, Charles Frederick Worth's couture and he instantly became famous in French republic though he had simply arrived in Paris a few years ago. In 1855, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of U.k. welcomed Napoleon III and Eugenie of France to a full state visit to England. Eugenie was considered a fashion icon in France. She and Queen Victoria became instant friends. Queen Victoria, who had been the fashion icon for European high fashion, was inspired past Eugenie's style and the fashions she wore. Afterward Queen Victoria also appointed Charles Frederick Worth every bit her dress maker and he became a prominent designer among the European upper class. Charles Frederick Worth is known as the begetter of the haute couture as afterward the concept of labels were also invented in the late 19th century as custom, fabricated to fit tailoring became mainstream.[26]

By the 1860s, when Europe was all about made-to-fit tailoring, crinolines were considered impractical. In the 1870s, women preferred more slimmer silhouettes, hence bodices grew longer and the polonaise, a brim and bodice made together, was introduced. In 1870s the Cuirass Bodice, a piece of armour that covers the torso and functions like a corset, was invented. Towards the end of Victoria's reign, dresses were flared naturally as crinolines were rejected by middle-class women. Designers such as Charles Frederick Worth were also confronting them. All these inventions and changes in style led to women'southward liberation as tailored looks improved posture and were more than practical.[25]

Home décor

Dwelling decor started spare, veered into the elaborately draped and decorated style nosotros today regard as Victorian, then embraced the retro-chic of William Morris as well as pseudo-Japonaiserie.

Contemporary stereotypes

Victorian Modesty

"The proper length for petty girls' skirts at diverse ages", from Harper's Bazaar, showing a 1900 idea of how the hemline should descend towards the ankle equally a girl got older

Many myths and exaggerations nearly the menstruation persist to the modernistic day. Examples include the thought of men's clothing is seen as formal and strong, women's as elaborate and over-done; clothing covered the unabridged body, and even the glimpse of an talocrural joint was scandalous. Critics contend that corsets constricted women's bodies and women's lives. Homes are described as gloomy, dark, cluttered with massive and over-ornate furniture and proliferating bric-a-brac. Myth has it that fifty-fifty pianoforte legs were scandalous, and covered with tiny pantalettes.

In truth, men's formal wear may have been less colourful than it was in the previous century, but bright waistcoats and cummerbunds provided a bear on of color, and smoking jackets and dressing gowns were frequently of rich Oriental brocades. This phenomenon was the result of the growing textile manufacturing sector, developing mass production processes, and increasing attempts to market fashion to men.[16] Corsets stressed a woman's sexuality, exaggerating hips and bust past contrast with a tiny waist. Women's evening gowns bared the shoulders and the tops of the breasts. The bailiwick of jersey dresses of the 1880s may have covered the torso, but the stretchy novel material fit the trunk like a glove.[27]

Home furnishing was non necessarily ornate or overstuffed. Still, those who could afford lavish draperies and expensive ornaments, and wanted to display their wealth, would often practise so. Since the Victorian era was one of increased social mobility, there were e'er more than nouveaux riches making a rich bear witness.

The items used in decoration may likewise accept been darker and heavier than those used today, only equally a matter of practicality. London was noisy and its air was full of soot from countless coal fires. Hence those who could afford it draped their windows in heavy, sound-muffling curtains, and chose colours that didn't show soot speedily. When all washing was done past manus, curtains were non washed as ofttimes as they might be today.

There is no actual bear witness that pianoforte legs were considered scandalous. Pianos and tables were often draped with shawls or cloths—only if the shawls hid anything, it was the cheapness of the furniture. There are references to lower-middle-class families covering up their pino tables rather than testify that they couldn't beget mahogany. The piano leg story seems to have originated in the 1839 book, A Diary in America written past Captain Frederick Marryat, equally a satirical comment on American prissiness.[28]

Victorian manners may take been as strict as imagined—on the surface. One merely did not speak publicly about sex, childbirth, and such matters, at to the lowest degree in the respectable eye and upper classes. However, as is well known, discretion covered a multitude of sins. Prostitution flourished. Upper-course men and women indulged in adulterous liaisons.

Gallery

-

A mid-Victorian interior: Hibernate and Seek by James Tissot, c. 1877

-

-

-

-

Come across too

- Victorian dress reform

- Women in the Victorian Era

- Victorian morality

- Charles Frederick Worth

- Victorian decorative arts

- Victoriana

Time periods

- 1830s in way

- 1840s in fashion

- 1850s in mode

- 1860s in fashion

- 1870s in fashion

- 1880s in way

- 1890s in fashion

Women'southward clothing

- Corset

- Corset controversy

- Tightlacing

- Bloomers

- Bodice

- Evening glove

Contemporary interpretations

- Steampunk

- Neo-Victorian

- Lolita

References

- ^ a b c d e f Breward, Christopher (1995). The Culture of Fashion. Manchester Academy Press. pp. 145–180.

- ^ "Gender roles in the 19th century". The British Library . Retrieved 21 Oct 2016.

- ^ Gernsheim, Alison (1963). Victorian and Edwardian Fashion - A Photographic Survey. New York: Dover Publications Inc. p. 26.

- ^ "History of Gloves in Fashion and Guild". fashionintime.org. 3 September 2020.

- ^ a b Goldthorpe, Caroline (1988). From Queen to Empress - Victorian Clothes 1837-1877. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c Goldthorpe, Caroline (1988). From Queen to Empress - Victorian Dress 1837-1877. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 32.

- ^ Goldthorpe, Caroline (1988). From Queen to Empress - Victorian Dress 1837-1877. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 39.

- ^ a b c d e f Steele, Valerie (1985). Victorian Fashion. Mode and Eroticism: Ideals of Feminine Beauty from the Victorian Era to the Jazz Age . Oxford Academy Press. pp. 51–84.

- ^ a b Goldthorpe, Caroline (1988). From Queen to Empress - Victorian Dress 1837-1877. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 26.

- ^ Goldthorpe, Caroline (1988). From Queen to Empress - Victorian Dress 1837-1877. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 45.

- ^ Audin, Heather (2015). Making Victorian Costumes for Women. Crowood. p. 45.

- ^ Laver, James (2002). Costume and Way: A Curtailed History. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 224–5. ISBN978-0-500-20348-4.

- ^ "Everglades National Park". PBS. Retrieved 7 Nov 2011.

- ^ Landow, George. "Men'due south breezy sporting dress, late 1880s and '90s".

- ^ "Victorian Men's Fashions, 1850–1900: Hair".

- ^ a b Shannon, Brent (2004). "Refashioning Men: Fashion, Masculinity, and the Cultivation of the Male Consumer in Britain, 1860–1914". Victorian Studies. 46 (4): 597–630. doi:10.1353/vic.2005.0022.

- ^ "The Colors of the Church Year". Consortium of Country Churches. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ The Metropolitan Museum of Art (7 September 2019). "Mourning Wearing apparel, 1894–95". The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art . Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Flemish region, Judith (2003). The Victorian House. London: Harper Perennial. pp. 378–83. ISBN0-00-713189-5.

- ^ Flanders, Judith (2003). The Victorian Firm. London: Harper Perennial. pp. 378–nine. ISBN0-00-713189-five.

- ^ Flanders, Judith (2003). The Victorian House. London: Harper Perennial. p. 341. ISBN0-00-713189-five.

- ^ Graham, P. "The Victorian Era". Digital Library of India.

- ^ Shrimpton, J. Victorian Fashion. Bloomsbury Shire Publications.

- ^ Aspelund, Karl. Fashioning Lodge. Fairchild Books.

- ^ a b Martin, Richard; Koda, Harold. Haute Couture. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Saillard, Olivier; Zazzo, Anne. Paris Haute Couture. Skira Flammarion.

- ^ Gernsheim, Alison (1981). Victorian & Edwardian Fashion: A Photographic Survey (New ed.). New York: Dover Publications. p. 65. ISBN0-486-24205-vi.

- ^ Marryat, C.B. (1839). A Diary in America: With Remarks on Its Institutions. Vol. 2. London, England: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 246–247. From pp. 246-247: "I was requested by a lady to escort her to a seminary for young ladies, and on being ushered into the reception-room, conceive my astonishment at beholding a square piano-forte with four limbs. However, that the ladies who visited their daughters, might experience in its full force the extreme delicacy of the mistress of the institution, and her care to preserve in their utmost purity the ideas of the young ladies nether her charge, she had dressed all these 4 limbs in modest little trousers, with frills at the bottom of them!"

Further reading

- Phipps, Elena; et al. (1988). From Queen to Empress: Victorian clothes 1837-1877 . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. ISBN0870995340.

- Sweetness, Matthew – Inventing the Victorians, St. Martin's Press, 2001 ISBN 0-312-28326-one

External links

- Victorian Style

- VictorianVoices.net – Fashion articles and illustrations from Victorian periodicals; extensive fashion prototype gallery

- Victorian myths

- Victorian manner, etiquette, and sports

- Background on "A Diary in America"

- Form and Way — the evolution of women's wearing apparel during the 19th century (many photographs)

- Educational Game: Mix and Match — build a 19th-century dress using a virtual mannequin

- "Victorian Dress". Way, Jewellery & Accessories. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved iii April 2011.

- Way detective: Fashion, Fiction and Forensics in nineteenth century Australian mode on Civilisation Victoria

0 Response to "Pictures of Late 1800s Girls Fashion"

Post a Comment